One of the first and most important financial questions to answer when discussing retirement is how much do I need to retire?

There are many ways to answer this question, but the 4% rule is one of the easiest. Quite simply, it says that the amount you can withdraw for a 30-year retirement is 4%.

Let’s dissect that for a minute. I will lay out how it’s used in the simplest terms, and then, for those interested, I will deep dive into the history and nuances of the “rule”.

The “rule” here is more a “rule of thumb“, and not any sort of legal-or-other rule.

I’m going to use some imaginary numbers, they might seem very high or very low, depending on your circumstances. Don’t let that distract you, it’s simply to illustrate the concept.

Let’s say you saved $1,000,000 and you had invested in a partial stock/bond portfolio (the specifics aren’t that important). The 4% rule says you can withdraw 4% of your total portfolio each year and still have money after 30 years.

4% * 1,000,000 = $40,000

This means that if you had $1,000,000, you could spend up to $40,000 a year and survive for 30 years. Great!

But, is $40,000 enough to survive for a year? This is completely dependent and unique to your living situation. One approach might be to calculate how much you spend on average per year over the last 5 years.

| Year 1 | $45,000 |

| Year 2 | $53,000 |

| Year 3 | $60,000 |

| Year 4 | $49,000 |

| Year 5 | $70,000 |

| Average Yearly Spend | $55,400 |

Now, 4% is the same thing as 1/25, so if you take your average yearly spend you can multiply it by 25 to get your number.

$55,400 * 25 = $1,385,000

Another approach is to take your monthly average. Let’s say it’s $5,000 a month. You would then multiply it out for the year, and then multiply it by 25.

$5,000 * 12 = $60,000

$60,000 * 25 = $1,500,000

That’s it! That’s how the 4% rule can be used to calculate your retirement number.

The 4% Rule Nuances (Important!)

Okay, now that you know how to use the 4% rule in the simplest method, it’s important to learn some of the nuances of the number. This is not the deep dive (that comes next), but some important aspects to know if you plan on using this for retirement. Here are a bunch of nuances:

- It assumes you’re in a 75% stock/25% bond portfolio mix. If you are anything other than this, it may not work for you.

- It does not account for fund fees. I will talk more about this in future posts, but you want the absolute lowest fund fees possible. Vanguard offers some funds with 0.04% fees (which is great!). Anything around 1% or higher is very expensive.

- You should adjust your withdrawal amount based on market performance. While 4% is the average spend, if the stock market is doing particularly poorly that year and you withdraw your normal 4%, this can increase your chance of running of money, or “portfolio failure”. Likewise, if the market is doing quite well, you can probably increase your rate.

- This only accounted for 30 years. If you plan to retire longer than 30 years, you should do further planning or reduce your withdrawal rate.

- This does not account for inheritance to heirs. If you want to leave money to your children, family, charitable organizations, or anyone else, you need to do more planning for that.

- This assumes you are investing in the US Stock market. This does not do as well in non-US-Stock markets.

- “Past performance is no guarantee of future results”. Just because this has worked for a very long time (1926 > 2009 with a high success rate), does not mean that will necessarily be true in the future. It very might be, but it might now.

- The first 10 years after retirement are the most important. When looking through the data, it shows that the result of the first 10 years accounts for about 80% of the success or non-success of that portfolio. That means that if you are more conservative in the first 10 years, you have a much greater chance of success for the remaining 20+.

- The more stocks you have the greater the potential for tremendous wealth or failure. 100% stock portfolios, per the data, often ended up with 2-7x as much value as the initial amounts. There were also, however, more failures that ended with 0. Many suggest starting with a portfolio with a high stock percentage and slowly shifting to a high bond percentage as you get closer to retirement. Some funds do that for you, which I will talk about in a future post.

- This doesn’t include any income/money outside of the portfolio. If you continue to work on the side, rent out your house, or receive Social Security, all of these things contribute to the amount of money you have but are excluded from this 4% Rule.

Some people have criticized the 4% Rule as not being conservative enough. If you have a 50% stock/50% bond mix, the success rate is 96%. That’s pretty high, but that also means that 4% of the tested portfolios “failed”, meaning they ran out of money before those 30 years. To combat this, you can reduce your withdrawal rate, from 4% to 3.3% or 3%.

The rest of the calculations would follow. If you were using 3.3%, rather than multiplying by 25 (100/4), you would multiply it by 30 (100/3.3). So, if your monthly spend was $5,000 a month:

$5,000 * 12 = $60,000

$60,000 * 30 = $1,800,000 (rather than $1,500,000 with 4%).

It should also be noted that some prefer a higher, less conservative withdrawal rate of 7%. Most consider this very risky, but it has worked out for many retirees.

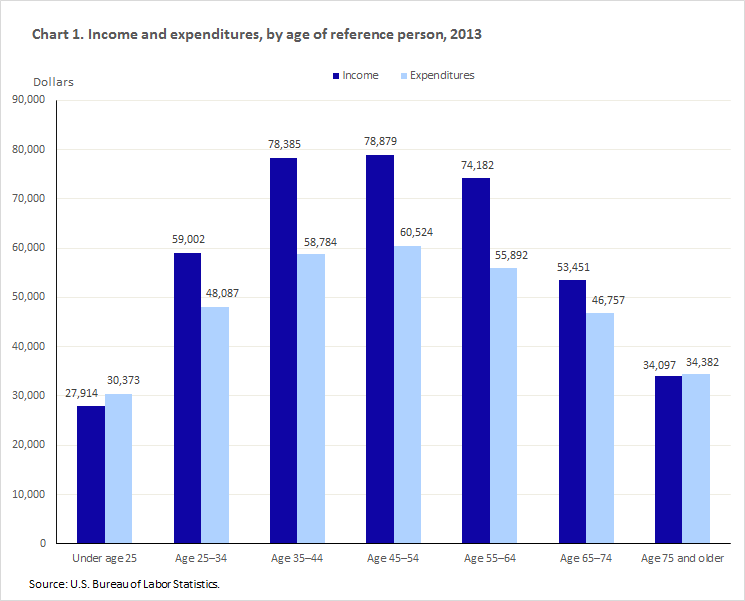

Another important point is that most people don’t spend the same amount each year for their whole life. Most people spend less as they get older, and so it could make sense to spend more in your early retirement years for quality of life as you expect to spend less as you get older.

History of the 4% Rule

You might want to stop reading here. This dives into the actual academic study and specifics of the rule. If that interests you, read on.

The 4% Rule came from a financial adviser in the 1990s by the name of William Bengen. The rule ended was also called the “Bengen rule”, and he later called it the SAFEMAX rate, or the “maximum safe rate” of withdrawal.

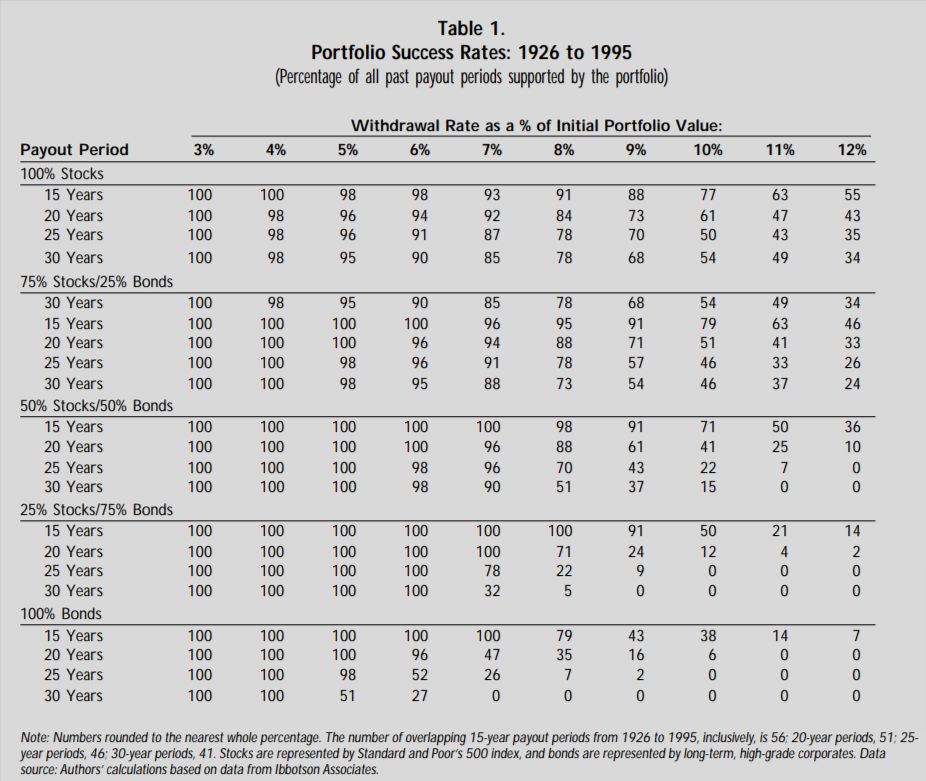

A few years after he shared this rule, Trinity College released a study, later dubbed the Trinity Study, that confirmed his work. This study did a comprehensive analysis of portfolios from stock market data between 1926 to 1995, and again from 1945 to 1995. They analyzed portfolios within several different cohorts:

| 100% Stocks | 75% Stocks/25% Bonds | 50% Stocks/50% Bonds | 25% Stocks/75% Bonds | 100% Bonds |

| 15 years | 15 years | 15 years | 15 years | 15 years |

| 20 years | 20 years | 20 years | 20 years | 20 years |

| 25 years | 25 years | 25 years | 25 years | 25 years |

| 30 years | 30 years | 30 years | 30 years | 30 years |

For each cohort, they computed the “portfolio success rate”, whether or not the portfolio still had money in it at the end of that period. They analyzed the amount of withdrawal rates from 3% to 12% for each of these cohorts.

Here is an example of one of those charts:

They mention that heavy-stock portfolios have a good chance of leaving large estates even with the very conservative 3-4% mark. They also noted that if you were only aiming for 15 years, you could have a much higher withdrawal rate of around 8-9%.

This study received much acclaim and critique, and they released a follow-up study in 2011 extending the data to go from 1926 – 2009. They chose a less conservative success number of 75% (meaning 25% of portfolios failed), updated to use a variable withdrawal rate based on market performance (withdraw more when the market is doing well, and less when it is doing poorly). That said, a 4-5% withdrawal rate was still considered a conservative and good number to shoot with.

In addition, William Bengen, the original creator of the 4% rule later changed it to the 4.5% rule in his book Conserving Client Portfolios During Retirement in 2006, based on further research. In a Reddit AMA, he answered the question that he considered 4% to be very conservative and believes it should last “forever” (beyond 30 years).

So, what’s the correct answer?

It seems that vaguely using something around 4% still holds up. In all scenarios, it depends a lot on your specific life and the results of the market, and the only thing we can predict accurately about the market is it will not be the same as in the past (but it likely will be similar).

In summary…

The 4% Rule is a rough guideline that is useful to get a quick idea of how much you need to retire. You can multiply your yearly spending by 25 and come up with “your number” (the amount you need to retire).

There are a lot of academic nuances that can help cater to specific scenarios that underly it all, but that’s not necessary when we’re just getting started.

For many, this is their first real step in their financial journey. There is now a target; a goalpost. You can shape many of your other financial decisions about getting to this number, whether that’s 30 years from where you’re at or only a couple. It might be eye-opening, maybe that number is much more than you thought. Maybe it’s much less than you thought and you can retire sooner.